Spanish Mustang: The History, The Romance

by Robin Doughman

The Spanish Mustang: a horse that conjures images of the past, images of chasing buffalo, of running with the wind, running free. Even now when I’m playing with my own mustangs out in my corral, you can see they have a sense of freedom, an attitude. An attitude that says I am Spanish Mustang.

If you ask them what they would really like to be in life, they will tell you they’d like to be a Spanish Mustang alpha mare. Considering the enormous possibilities of how we could have turned out, that would be a pretty good deal. It suits them just fine. There’s nothing else they would rather be.

I know there are a lot of good horses out there of all sizes, colors and breeds, and a lot of them can do all kinds of incredible things. You will not find a good horse in a bad color or a bad breed. But in the end, one will find there is no better horse than a Spanish Mustang. A good mustang will match any good horse.

So, what is a Spanish Mustang? How did they get here? Where did they come from?

The true Spanish Mustangs, which are relatively few in number, are directly related genetically to the horse that Columbus brought over on his second voyage in 1493. They came from the well-known Spanish horses of the time with a background of Jennets and Barbs, bred to perfection for war, full of stamina with strong Andalusian bloodlines. No other breed in the world at the time was more suited for what they would become.

The best of the best were selected and crammed into an unimaginable hell for a two-month trip of total horror. Those that survived were put ashore on an island in the Caribbean. Somehow, they recovered from this experience and prospered.

Over the next twenty-five years, their numbers grew. They became accustomed to the climate. The Spanish and their magnificent horses were now ready to conquer Mexico.

The Aztec were never consulted about this, even though they played an important role in the story. But another monumental change this contact brought about was to establish the horse on the Mexican mainland.

At this point they were not yet mustangs. They were still the renowned Spanish horse, the horse of the Conquistadors.

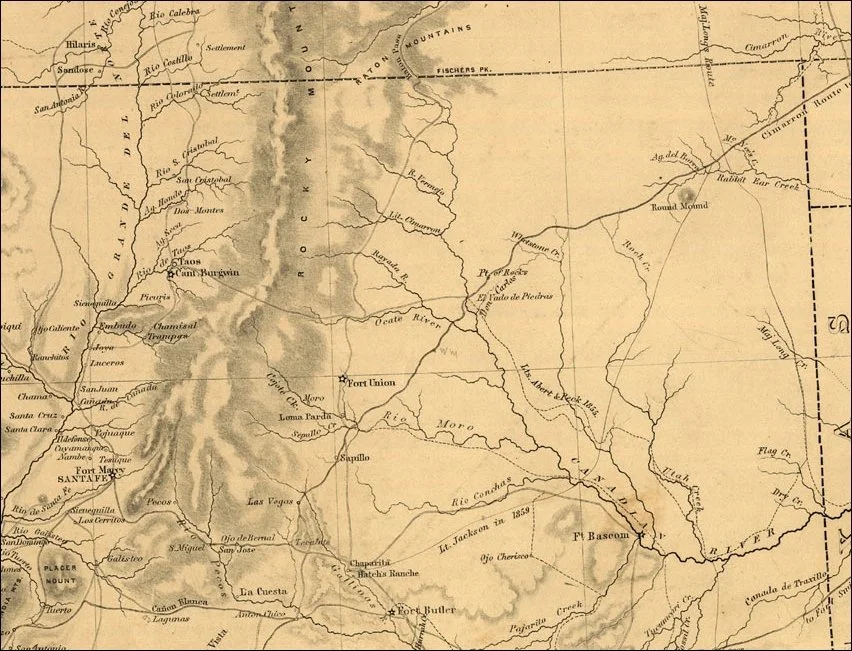

It took another seventy years for horses to reach New Mexico, with the arrival of Oñate who settled near Santa Fe in 1598. This was when the distribution of the horse to the Native Americans began.

The very first tribes to acquire horses were the Pueblo, Jicarilla Apache, and the Ute. Other tribes followed close behind. This was also the time many horses escaped and became free of human bonds altogether. Both of these events contributed to what would now be the Spanish Mustang.

The typical Indian pony of these times would be described as fourteen hands tall; light in build; good legs; short, strong back; full barrel; sharp, nervous ears; and bright, intelligent eyes. Mustang bands were full of color, which the Indians preferred—red and blue roans, paints, appaloosas, white, buckskins.

We all know horses can change a person’s life. Those early mustangs changed an entire culture. The Native Americans of those times lived with their horses and worked with their horses and they became each other. They lived as horse nations. They became legendary.

As mountain men began to roam the West, they acquired mustangs from local populations. These reckless men admired mustangs for their sure-footedness in the mountains and their ability to scramble through the rocks. They carried these pathfinders in search of adventure and along new trails.

Mustangs from the Shoshone were crucial to the Lewis and Clark expedition. Fremont would not have succeeded without these tough little horses that could endure all the hardships that were being asked of them.

In the late 1840s and 1850s, the mountain men and their way of life began to die out. The mustang survived. At that time there were approximately two million mustangs in the West, mostly in Texas and Oklahoma. Life was good for the mustang.

In the 1850s, Easterners started heading west, guided by old mountain men who had managed to stay alive long enough to help participate in the settling of their beloved Wilderness.

With the settlers also came Eastern horses, not suited for the West at that time. But they kept coming anyway.

The year 1860 brought a reversal of Western growth for half a dozen years or so. After the Civil War, growth began again with a vengeance. Earlier, Thomas Jefferson, along with most people of his era, had believed it would take forty generations to settle the West. How different would it have been if they had been correct?

When young ex-soldiers returned to Texas after the Civil War, they found that wild cattle had spread all over the place and they were worth money on the hoof. The cowboy at this time came to be one of the major icons of the West, a true ambassador of romance. His transportation of choice, of course, was the Spanish Mustang.

Even with more Eastern horses arriving, the mustang was still the only horse tough enough for the job. The Indian pony turned into the cow pony. The cowboy and the mustang became intertwined. They became one, similar to the ways in which the Indians embraced the mustang. Cowboys and mustangs became the stuff of legend, inspiring innumerable songs, books and movies.

All the while, Eastern horses were coming west, and people bringing them were bringing along the idea that ‘mine is better than yours’, so fences went up. The wild mustang was in the way. After hundreds of years of glory, many now considered them as nothing more than vermin.

Powerful people convinced our government to take action and get rid of the mustang. One plan was to bring in stallions to breed the mustangs out of existence. But the Indians captured the stallions and gelded them so the mustang breed would remain the same. So those who considered the mustang inferior came to the conclusion that the only successful way to control the grassy plains was to turn the matter over to the Army.

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, thousands upon thousands of the mustangs were rounded up, corralled, and shot with machine guns, murdered en masse, one herd after another. They were left to rot where they were shot.

At about this same time, a young cowboy and surveyor came on the scene. Robert Brislawn lived in northeast Wyoming. He believed in the mustang. He had used them in his work, and they took care of him. Brislawn saw the need to save the icon that had played such a pivotal role in American history.

He and his family traveled the West, much of it on horseback, starting a lifelong search for horses of pure Spanish blood. They collected horses from isolated Nevada ranches and from the northern Cheyenne and Ute.

One of the legends of the early days of the Brislawn endeavor is Monty, a buckskin stallion captured in Utah, sired with a mare from the Ute reservation. Two of the best early colts of the Spanish Mustang recovery were born from this union. Monty escaped back into the wild, taking his mares with him, never to be seen again—but his colts remained, and became the core of the Cayuse Ranch Spanish Mustangs.

Bob Brislawn

Robert’s son, Emmett, will tell you, “These horses think. It’ll scare you how they think.”

And indeed they do. Of all their incredible qualities, their intelligence is what comes through when you get to know them. Their intelligence was fundamental in their survival, and their solitary survival experience set them apart from all the other horses of the Americas.

When examining what it really means to be a horse, mustangs are our best example, and they have the answer to questions of survival itself.

The Cayuse Ranch was the homestead of Bob Brislawn. It is still called home by Emmett and his family as they continue working to preserve the Spanish horse. The Brislawn family is the principal force in saving our country’s first horse from extinction. Mustangs still run free across the plains like their ancestors did hundreds of years ago.

Emmett Brislawn

Robin Doughman passed away in 2019. Robin was a member of the Spanish Mustang Foundation. He was responsible for starting our youth clinics and helping the Foundation in numerous ways to preserve the Spanish Mustang horse. He worked with founders Donna Mitchell and Doug Lanham to preserve and promote the Spanish Mustang. The foundation is proud to be a small part of the Brislawn dream.

“When examining what it really means to be a horse, mustangs are our best example, and they have the answer to questions of survival itself.”

—Robin Doughman